WORKING WITH INDUSTRIES AND UNIVERSITIES

There is another event, however, that relates to what was done and how NASA proceeded with Apollo. This event was a visit from a sophisticated senior official of a large corporation holding many aerospace contracts. He hit me right between the eyes with the question: "In the award of contracts are you going to follow 100 percent the reports of your technical experts, or are there going to be political influences in these awards?" My answer was just as direct: "In choosincy contractors and supervising our industrial partners, we are going to take into account every factor that we should take into account as responsible government officials."

|

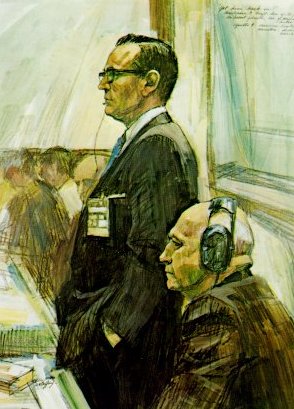

M. McCaffrey, CHRIS KRAFT AND DR.GILRUTH, mixed media on paper |

This meant that NASA officials would be required to meet President Kennedy's basic guideline - that we would not limit our decisions to technical factors but would work with American industry in the knowledge that we were together dealing with factors basic to "broad national and international policy". This also became our basic guideline for relations with universities and with scientists in the many disciplines that became so important a part of Apollo.

We constantly endeavored to set our course so that all who participated in Apollo could grow stronger for their own purposes at the same time that they were doing the work to succeed in NASA's projects. As they worked under NASA support, we were determined not to deplete their capability to achieve those goals that were important to them. In essence, our policy was to help them build strength so they could add to the Nation's strength.

Historians will find many lessons in the Apollo program for the managers of future large-scale enterprises. It was a new kind of national venture. Suddenly and dramatically it brought men of action and men of thought into intimate working relationships designed to solve a large number of extremely difficult scientific and technical problems. It was a major challenge to legislators, scientists, and engineers.

After a careful study of the way we conducted our work, Dr. Leonard R. Sayles and Dr. Margaret K. Chandler of the Graduate School of Business at Columbia University wrote:

"NASA's most significant contribution is in the area of advanced systems design: getting an organizationally complex structure, involving a great variety of people doing a great variety of things in many separate locations, to do what you want, when you want it - and while the decision regarding the best route to your objective is still in the process of being made by you and your collaborators."

|

Robert McCall, GEMINI RECOVERY, watercolor on paper |

Although our goal was clear and unambiguous, to reach it we had to use rapidly developing technology that in turn was based on rapidly increasing scientific knowledge. This required our organization to be highly flexible, and it was altered when unexpected developments made this necessary. As Mercury phased into Gemini, and Apollo reached its peak effort, NASA's work force grew to 390,000 men and women in industry, 33,000 in NASA Centers, and 10,000 in universities. By 1969, the year of the first lunar landing, this total had been reduced by 190,000. By 1974, it was down to 126,000. This is certainly an administrative record.

No more flights to the Moon are scheduled now, and future ones will undoubtedly be made differently, but the Apollo program has not really ended. Instruments placed on the Moon by the American astronauts are still transmitting important data to scientists throughout the world. We know much about how the Moon is bound to the Earth by invisible gravitational fields, and how both are similarly bound to the star we call the Sun. Daily, men and women are learning more about that star, and about the whole universe.

| Next |