Apollo Expeditions to the Moon

WHAT HAPPENS TO EX-ASTRONAUTS?

The exclusive-story gambit almost ended when the Kennedy Administration took

over, and Kennedy's press secretary actually announced there would be no more

contracts after Mercury ended. But John Glenn went sailing with the President one

summer day in 1962 and enumerated the costs and risks that came with fame. The

President relented and more contracts were signed after the Second Nine entered, this

time with not only Life but also Field Enterprises. But as more astronauts were

selected, the pie sliced thinner until finally each astronaut was receiving only $3000

per year for his literary output. One last surge came with Life's European syndication

of the stories of Apollo 8 through 11 in 1969, which brought about $16,000 for each

of sixty astronauts and widows.

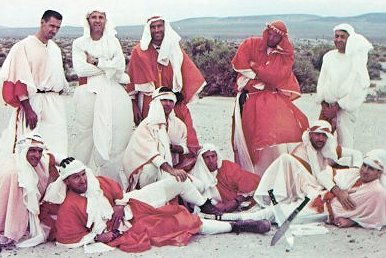

| | |

Desert survival training

was part of the regular

program of what-ifs. If

any flight had ended with

an emergency landing in

a desert, sun-protective

dress and tents could

have been fashioned from

spacecraft parachutes.

The astronauts were

taught the best tricks for

survival in the desert. Left

to right, seated: Borman,

Lovell, Young, Conrad,

McDivitt, White. Standing:

training officer Zedehar, Stafford, Slayton,

Armstrong, and See.

|

A principal advantage of the contracts was the insurance, $50,000 worth from

both Life and Field for each astronaut, and the widows of the accident victims were

left with nest eggs. Congress might have been able to provide extra income and extra

insurance, but the Vietnam War got in the way, and who was to say a man dying in

space was more deserving than one who stepped on a land mine in a jungle path?

Unfortunately, this easy money led, directly or indirectly, to money acquired less

scrupulously when the Apollo 15 astronauts sold 400 unauthorized covers to a German

dealer in exchange for $8000 each (the dealer got $150,000). The three returned

the money, and were subsequently reprimanded. It also turned out that each of fifteen

astronauts had sold 500 copies of his signature on blocks of stamps for $5 apiece,

without saying anything to bosses Slayton and Shepard about it (five of the fifteen

gave the proceeds to charity). Deke and Al were incensed, but threw up their hands.

If a man has a claim to owning anything, it is his own signature. Nevertheless NASA

put a stop to this business and also placed heavy restrictions on what astronauts

could and could not carry into space.

Homogeneous the astronauts never were. Frank Borman learned to fly a plane

before he was old enough to get a driver's license, and so did Neil Armstrong, but at

the same age Dick Gordon was considering the priesthood, Mike Collins was more

interested in "girls, football, and chess" than in planes, and Jim Irwin had never flown

until he rode a commercial aircraft to begin flight training.

John Glenn went into politics and, after several disappointments, was elected

U.S. Senator from Ohio on the Democratic ticket in 1974. Alan Shepard's $125,000

from the Life and Field contracts became the egg that hatched a fortune in real estate.

Borman, success-prone as always, spent a semester at Harvard Business School, went

to work for Eastern Airlines, and became its president. For several years Donn Eisele

served as director of the Peace Corps in Thailand, which was as different from Dick

Gordon's executive job with the New Orleans Saints football team as was Mike Collins's

directorship of the Smithsonian Institution's Air and Space Museum. Armstrong

became a professor of engineering at the University of Cincinnati, Ed Mitchell

founded an organization devoted to extrasensory perception, and Jim Irwin became a

fundamentalist evangelist. Jim McDivitt became an executive of Consumers Power

Company in his home town, Jackson, Mich., and Jim Lovell stayed put with the

Bay-Houston Towing Company.

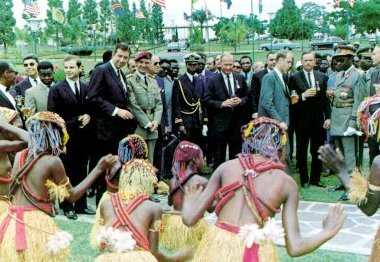

| | |

Saying a few words to

a sea of friendly faces

was the lot of the Apollo

11 astronauts, whose

world tour aboard Air

Force One took them to a

dizzying 24 countries in

45 days.

|

| | |

Children of Kinshasa

dance a special welcome

for the men from the

Moon. Tact, diplomacy,

an iron constitution, and

a knack for public speaking

were what the astronauts

needed on tours.

|

Once in awhile some them still turned up on television or radio: Schirra plugging

the railroads, Aldrin Volkswagens, Armstrong and Carpenter banks, and Lovell insurance.

Collins was offered $50,000 to advertise a beer but he turned it down, "although

I like beer". Lest he appear too upright, Collins did confess that he once made an

unpaid commercial for U.S. Savings Bonds, although he had never seen one in his life.

If the astronauts sometimes dwelt in an aura of public misconception, they

nonetheless performed dazzling feats with skill and finesse. You may search the

pages of history in vain for deeds to match theirs, and many years will pass before

similar feats occur again. All hail, then, to these daring young men who married

technique to valor and in barely a decade transformed the impossible into the

commonplace.

|